Editor’s note: This article is part of Something Ventured, an ongoing series by Crunchbase News examining diversity and access to capital in the venture-backed startup ecosystem. Earlier, we reported on the growth but remaining challenges for venture funding to Black startup founders, looked at the state of funding to startups founded by Black women, and at Georgia, the state that invests the highest percentage of its VC funding into Black entrepreneurs. Access the full Something Ventured project here.

Goodr founder Jasmine Crowe was pitching her startup, which works to end food waste, to an investor when she mentioned that she attended an HBCU, or a historically black college and university.

There are more than 100 educational institutions recognized by the U.S. Department of Education as HBCUs, including Howard University, North Carolina A&T State University, and Florida A&M University, to name a few.

But instead of asking which HBCU, the investor didn’t seem to understand what an HBCU was.

“They said, ‘Oh where is that at?’ Not even understanding that HBCUs were a lot of schools,” said Crowe, who graduated from North Carolina Central University. “I think that alone is one of the issues right there—a lot of times there’s just no understanding of what an HBCU is.”

Grow your revenue with all-in-one prospecting solutions powered by the leader in private-company data.

According to Crunchbase data, Goodr is one of at least 144 venture-backed startups founded by alumni of HBCUs. Those startups have raised nearly $953 million over time. Still, the number of VC-backed companies founded by HBCU alumni is relatively small, and the challenges founders from HBCUs face are part of the greater issue of lack of funding to Black startup founders.

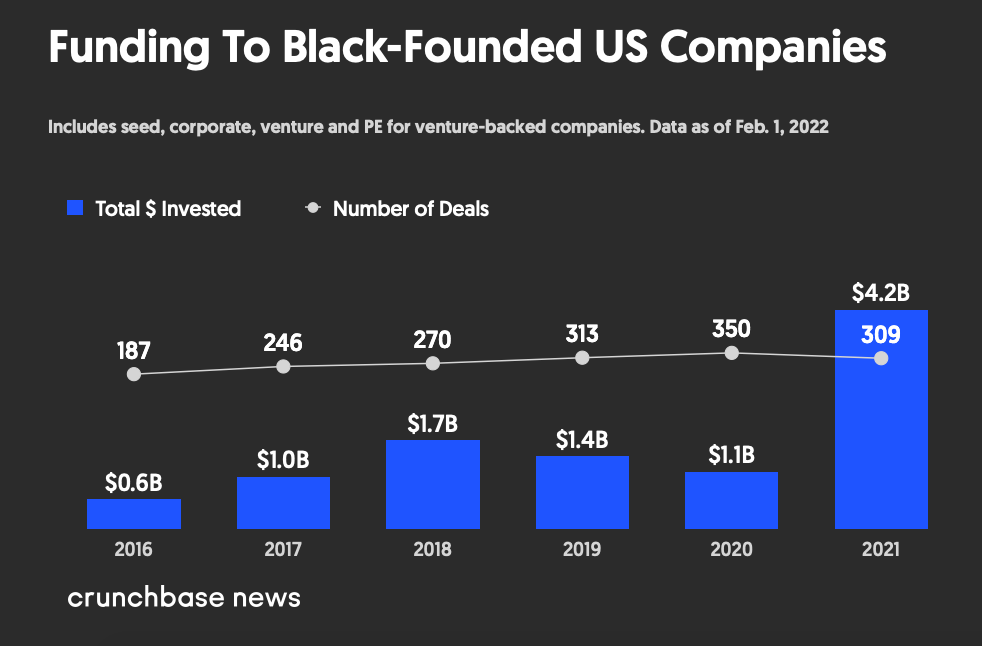

According to Crunchbase data, U.S.-based companies founded by Black entrepreneurs raised around $4.2 billion last year, up more than 281 percent from the year prior. While it’s grown significantly in dollar terms, that figure represents only 1.3 percent of the total venture dollars raised by U.S. companies last year. Black women in particular face immense challenges in raising startup capital.

Those challenges have deep roots that run back to the United States’ history of slavery, according to Tiffiany Howard, an associate professor of political science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas who has researched Black entrepreneurship in the U.S.

After the abolition of slavery, African American entrepreneurship thrived with thousands of Black-owned businesses in the United States, Howard said.

But after Reconstruction and during the Jim Crow era, many of those businesses were destroyed, and there wasn’t an opportunity for those affected to start over because of a lack of resources and government support, she said.

That, in a way, made entrepreneurship seem less attractive to African Americans.

“There was the narrative that entrepreneurship wasn’t the way to go,” Howard said. “Education was the way to advance.”

For a long time, many HBCUs didn’t have entrepreneurship centers because there was a prevailing notion that education was a more sure path to financial stability, she said.

The narrative that entrepreneurship could be a path to financial security for African Americans only started becoming more prominent in the last decade or so. The Great Recession played a role in that shift, as did mounting student debt.

“With the student loan debt that also entered the picture—and how hard it is for students who are graduating now and seeking jobs—that was another reason why the entrepreneurship narrative has become more salient since 2007, 2008,” Howard said.

Because of risks that come with starting a company, many HBCUs are driven to make sure their graduates get into careers that are considered safer, according to Chelsea Roberts, chief operating officer of HBCU.vc, an organization that helps develop the next generation of investors to increase access to capital for Black and Brown founders.

That focus makes sense: Schools want to spur wealth creation for their graduates, and that often means helping their students find stable, financially secure careers.

“A lot of our HBCUs really want their students, for a lot of great reasons, to get into well-paying jobs,” Roberts said. “But a well-paying job isn’t being an entrepreneur or founder at 21 or 22.”

The two main challenges founders from HBCUs face when raising money for startups is networking and access to capital, according to Roberts.

Those challenges start from the very beginning of a founder’s journey and stem from broader racial wealth disparities that persist in the United States. According to the Brookings Institute, the median white household in 2019 had nearly 8x the wealth of the typical Black household.

Roberts pointed out that at the earliest stages of building a company, many tech founders raise money from family and friends. The average Black student or recent graduate, whether or not they went to an HBCU, doesn’t have access to that kind of seed capital, she said.

“The challenge really is at the earliest stages not being able to access capital because your family, your friends, your network, doesn’t have those disposable dollars to give you to fund your company,” Roberts said, an issue that she said represents “a huge barrier.”

Many founders who went to HBCUs also don’t have the right network to start a company; knowing investors, mentors and others who can provide guidance. That, too, goes back to the wealth gap: Even though HBCUs do have strong networks, it can still be difficult for graduates to raise money from their connections.

Rashaun Williams, a general partner at Manhattan Venture Partners and a Morehouse College alumni and adjunct professor, also pointed to the wealth gap as a major barrier for students. Typically, when a startup receives VC funding, it’s after the founder has put in his or her own money, and then either built the product themselves or hired someone to help build the product, Williams pointed out.

“These people coming from wealthier backgrounds can raise $500,000 to $1 million, build a product, hire a team, get customers, get some traction and then they can say, ‘I want to go to Silicon Valley,’” Williams said.

In contrast, many minority founders are pitching investors with just a Powerpoint presentation, according to Williams, who was also a founding general partner at QueensBridge Venture Partners, the VC firm co-founded by rapper and entrepreneur Nas.

There’s often a lack of knowledge in the community about what’s required to get funding for a company as a first-time founder, he said, because the Black community has been blocked out of those markets for generations.

The lack of funding to Black entrepreneurs is often simply categorized as racism, but often the direct reason a Black-founded company doesn’t get funding is because of a lack of traction, said Williams, who teaches a class on venture capital investing at Morehouse.

And the lack of traction goes back to not having the resources to raise a family-and-friends round (again, due to the wealth gap), hire a team and grow the company to the point that outside VCs would be willing to invest.

“Most people don’t even understand that a lot of the successful founders are raising money before they even get to Silicon Valley,” Williams said. “They think they’re coming up with an idea and thinking they’re getting $5 million for that idea.

“We’re teaching kids the rules to the game and we’re helping them use their extended network, their social network to (bridge) that family, friends and fools gap,” he added.

Building a venture-backed startup is “about convincing people to buy into your idea,” according to UNLV’s Howard. And since venture capitalists and angel investors are often white men, it’s more difficult for Black or female founders to convince those people that their idea could be a viable business.

“(There is a) cultural barrier, the gender barrier, there to try and convince someone who is unfamiliar with these intricate practices that happen within communities, that this is something the community would buy or consume,” Howard said.

Part of the solution, according to Williams, is nurturing the desire for entrepreneurship and showing young Black students how it could be a viable career, then giving them the skill set to succeed.

Seeing cultural icons from the Black community like Jay-Z and Nas who are successful investors also inspires more college students to become involved in startup entrepreneurship, whereas a decade ago that wasn’t the case, he said.

“Culturally, it wasn’t the cool thing to do,” Williams said. “So you have to look at our cultural icons and how they’re changing the game for us.”

“No. 1, you have to have the desire, No. 2, you have to have the resources, the ecosystem,” Williams said. “No. 3, there has to be some pathway from, ‘I’m interested’ to ‘Let’s build a startup.’”

There are also many benefits to being a founder from an HBCU. Both Roberts and Howard pointed to the loyalty of the HBCU network.

“The HBCU network is so strong and it’s literally like a family who will come after and, of course, those who came before you and, because you graduated from their school, had the same professors, lived in the same dorm rooms, are willing to help and willing to introduce you to other folks and be supportive; that is a huge plus of being a founder from an HBCU,” Roberts said.

For Goodr founder Crowe, one of the benefits of attending an HBCU was learning how to stretch her resources—a handy skill when launching a startup.

“I did push myself to do more even if I had less,” Crowe said. “I think that’s something that just kind of came from being an HBCU student. We learn we have to work twice as hard to have half as much.”

Howard emphasizes that students who want to be entrepreneurs should not feel discouraged from attending an HBCU because of the challenges that may arise as they work toward building a company.

The amount of funding going to Black founders has also increased because of changes in crowdfunding regulations and more corporations taking interest in Black entrepreneurship and investing in minority-owned micro VCs, Williams said. That’s helping bridge the gap in capital from family and friends.

In recent years, several HBCUs have opened entrepreneurship centers and formed partnerships with businesses to support students. Howard University announced last year that in partnership with PNC Bank it would open an entrepreneurship center to support Black business owners.

The idea behind Morehouse College’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center, which opened about two decades ago, is that students—whether they plan to start a business or not—graduate with an entrepreneurial mindset. That involves teaching problem-solving, whether for issues in a business or societal problems, according to executive director Tiffany Bussey.

The center also started teaching the history of Black entrepreneurship two years ago to “build a curriculum that speaks to who we are,” Bussey said.

Some of the center’s programming includes meetups, a speaker series of young Black entrepreneurs so students can see founders who look like them, a monthly pitch competition in which entrepreneurs in the community sign up as judges, but also stay on as mentors to students, and internships with startups, Bussey said.

HBCUs also offer the benefit of being an intellectual safe space and providing a community of people who look like you, Bussey said.

And the attributes that help someone become a successful entrepreneur—confidence, tenacity, adaptability—are traits that many Black students already have, by virtue of overcoming the challenges that many African Americans in the United States face, Bussey said.

“We come to this with these innate abilities,” Bussey said. “We just have to learn the fundamentals now to be able to do that.”

Those challenges include ongoing racism and even threats of violence: More than a dozen HBCUs were the subject of bomb threats on Tuesday, the start of Black History Month.

Morehouse was the only college Williams applied to. It’s the place that taught him how to be a man, a leader in his community, and be proud of who he was because of his ancestry, he said.

Then, it gave him opportunities.

“Morehouse was the first investor in me–that family and friends round,” Williams said. “And then Morehouse sent me over to Wall Street and I was able to build wealth and confidence and then I was able to build my own VC fund with Nas…We’re taught that we’re responsible for our community. It’s not philanthropy or charity to give to our community—it’s an obligation.”

Illustration: Dom Guzman

Stay up to date with recent funding rounds, acquisitions, and more with the Crunchbase Daily.

Find the right companies, identify the right contacts, and connect with decision-makers with an all-in-one prospecting solution.

Editorial Partners: Verizon Media Tech

About Crunchbase News

Crunchbase News Data Methodology

Privacy Policy

Terms of Service

Cookie Settings

Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Info

CA Privacy Notice

Company

Careers

Partners

Blog

Contact Us

Crunchbase Pro

Crunchbase Enterprise

Crunchbase for Applications

Customer Stories

Pricing

Featured Searches And Lists

Knowledge Center

Create A Profile

Sales Intelligence

Sales Prospecting Guide

Sales Prospecting Tools

© 2024 Crunchbase Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Startup Founders From HBCUs Overcome Funding Challenges With Grit, Determination – Crunchbase News

More Stories

6 Things Kamala Harris Has Shared About Her Heritage – TODAY

HBCU Professor Releases New Book, “Gifted and Black: 365 Days of Black History” – BlackNews.com

The 44 Percent: Florida’s Emancipation Day + Biden’s billion-dollar promise + A Black pioneer in space – Miami Herald